When Empathy Becomes Selective: What the Tina Peters Case Reveals About Modern Justice

In today’s justice system, something unsettling is happening.

People who commit real, tangible harm – assault, looting, repeated property crimes – are increasingly met with empathy, diversion programs, and early release. Prosecutors cite trauma. Judges cite social context. The language of rehabilitation dominates.

Yet when the offence involves political dissent or institutional defiance, empathy evaporates. Instead, punishment escalates.

The case of Tina Peters, a former Colorado county clerk in the USA, sentenced to nine years in state prison for her role in breaching voting systems related to the disputed 2020 U.S. election, is not merely an election story. Through a criminal justice reintegration lens, it is something far more revealing:

It is a story about how punishment has quietly shifted from addressing harm to enforcing compliance.

The Reintegration Question We’re Not Asking

As someone who works with justice-involved individuals, I was trained to ask a simple but foundational question:

What harm is incarceration meant to address?

The state argues that Peters’ breach of voting protocols undermined public trust, a serious form of institutional harm. That is not in dispute. But a justice system based on proportionality must weigh abstract harm against physical reality.

In Peters’ case:

- There was no allegation of physical violence.

- No allegation of theft for personal financial gain.

- No allegation of direct injury to another human being.

Yet the sentence imposed, nine years, rivals or exceeds those handed down for violent crimes in jurisdictions now committed to “restorative justice.” Does a bureaucratic breach truly warrant a decade of life, while those who break bones and destroy livelihoods walk free?

That contradiction deserves scrutiny.

A Growing Double Standard in Criminal Justice

Modern criminal justice increasingly distinguishes not between violent and non-violent conduct, but between approved and unapproved beliefs. To see this, we only need to look at the numbers.

The Colorado Contrast

In Colorado, the very state where Peters was sentenced, the presumptive prison range for Involuntary Manslaughter – killing a human being through reckless conduct – is just two to six years. Similarly, Second-Degree Assault, a charge that often involves significant bodily injury, carries a standard presumptive range of two to six years.

A person can end a life or maim another human being and potentially serve less time than Tina Peters received for using someone else’s security badge to give an expert access to the Mesa County election system and deceiving other officials about that person’s identity. She wanted to prove that the 2020 election was rigged.

The “Quiet Absolution” of Rioters

Contrast this severity with the treatment of political unrest in 2020. In Portland, federal prosecutors dismissed more than one-third of all cases stemming from the riots, including felony charges for assaulting federal officers and attempting to burn down the federal courthouse.

The Decriminalization of Theft

In California, under Proposition 47, theft under $950 is treated as a misdemeanour. The result? Arrest rates have plummeted, and the clearance rate for property crime has dropped to roughly 7%, effectively deprioritizing the protection of private property to avoid “over-incarceration.”

The message is unmistakable:

- If you burn a courthouse, you are “venting frustration.”

- If you steal for profit, you are a “victim of circumstance.”

- But if you question the integrity of an election system, you are a danger to the state who must be buried under the jail.

This is not rehabilitation. It is exemplary punishment.

When Belief Becomes the Crime

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the Peters case is not the conviction itself, but what followed.

Her continued belief that the 2020 election was flawed has been cited as evidence of defiance rather than opinion. In effect, belief persistence has become an aggravating factor.

The system calls it “lack of remorse,” but in practice, it functions as a penalty for dissent. Because she refuses to recant her political view, her sentence was multiplied. She is not in prison merely for what she did, but for refusing to say what the state wanted to hear.

A justice system committed to rehabilitation must accept that:

- People can hold wrong, unpopular, or even offensive beliefs.

- They can do so without forfeiting their humanity or deserving disproportionate punishment.

When belief itself becomes evidence of dangerousness, the line between law enforcement and thought policing begins to blur.

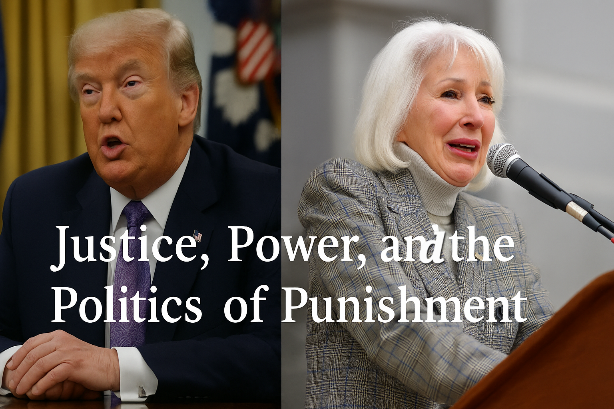

Trump’s Pardon and the Bigger Issue

President Trump’s announcement of a federal pardon for Peters does not erase her state conviction. Nor does it resolve the legal questions surrounding her case.

But it does expose a deeper truth:

Even imperfect political actors sometimes recognize when punishment has drifted from justice into symbolism.

One can disagree with Trump’s motives and still question whether this sentence reflects proportionality, public safety, or reintegration principles. Those positions are not mutually exclusive.

A Question for the Diaspora and for Justice Professionals

Across the diaspora, many of us come from societies where:

- Law was weaponized against dissent.

- Courts served power before justice.

- Prisons were tools of political discipline.

Western democracies have long claimed to be different. But cases like this raise an uncomfortable question:

If the justice system can forgive violence but not dissent, if rehabilitation applies to criminals but not critics, and if belief itself becomes punishable –

Who is the system really trying to protect?

That is not a partisan question. It is a justice question.

And it is one the diaspora, of all people, should not ignore.